Clinical Trial Design

Episode Notes

Types of Trials

Screening trials

Designed to improve the discovery of early, asymptomatic disease

Should both identify individuals and prescribe treatment

Prevention Trials

Designed to reduce the effects of a disease

Primary prevention

Investigate ways to reduce the risk of disease occurring

I.e. vaccine trials

Secondary prevention

Designed to identify treatment of early-stage disease, thereby reducing risk of progression to later stage disease

Tertiary prevention

Designed to identify interventions that decrease the morbidity and/or mortality associated with a disease after people have been diagnosed

This is the majority of oncology trials

Phases of Drug Development

Preclinical

Studying the drug in a basic science lab - tumor cell lines, tissue cultures, animals

Phase I

“Safety phase”

Aimed to identify dosages of drugs - specifically, maximum tolerated dose (MTD)

Goal is to identify recommended dose level (RDL) OR recommended phase II dose (RP2D) OR no recommended dose if none of the effective doses are tolerable

Enroll small groups of patients who are administered increasing doses of the developing drug

Clinical responses also recorded but not primary aim

Phase IB Expansion

Take a specific dose or specific subgroup from the initial portion of the phase I trail, then expand its use in that group

Often randomized to two different doses

If no difference in efficacy, then FDA will require the lower dose for next phases

Phase II

“Efficacy Phase”

Investigates whether an agent produces a sufficiently robust response to move to phase 3

How to measure efficacy?

RECIST criteria

Time to first progression or recurrence

Smaller than phase 3 trials and typically not placebo-controlled

Primary outcome usually overall response rate (not PFS or OS)

Phase IIa

Compare response rates to comparative historical control

Multi-arm compares multiple experimental regimens against SOC response rate for that disease site/stage/setting

Phase IIb

Compare response rates of experimental drug to response in patients given SOC in real time

Commonly used for biomarker-specific/targeted therapy trials (often there isn’t an accepted historical response rate)

Safety Lead-In

Small cohort

Allows for quicker movement from phase I to phase II

Can be used for new drug combinations sometimes when toxicities are not anticipated to be that severe

If not severe, then can expand to phase II trial

Example is chemo + IO combination trials

Phase III

Designed to determine efficacy compared to SOC in a specific patient population

Aim is to change SOC and to get FDA approval

Types of Phase III

Superiority: is the intervention better than the SOC?

Accounts for majority

Non-inferiority: is the intervention not worse than the SOC?

Designed to demonstrate that there is something better (i.e. side effects, QOL, cost) with non-inferior oncologic outcomes (i.e. PFS, OS)

Equivalency: rarely used in oncology

“Best”: randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled

Randomization

Assigning participants randomly to the control arm vs experimental arm

Reduces selection bias

Examples: stratified randomly permutated blocks, dynamic treatment allocation

Blinding

Non-disclosure of control vs experimental arm

Single - just the patient

Double - patient and administering physician

Triple - patient, physician, statistician

Placebo

Another way to reduce bias and strengthen integrity of trial

Adaptive Trials

Allows quicker movement from Phase II to Phase III

Allow trial design to change during the trial, based on interim data

Saves resources, allow the trial to progress quicker w/o having to design, accrue, and get approval for two separate trials

Phase IV

Conducted after regulatory approval to evaluate long-term effectiveness, rare adverse events, and real-world outcomes

Clinical Trial Outcomes/Endpoints

Typical Primary Endpoints

Phase I/II: Overall Response Rate

Phase III+: Progression free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), or progression free survival 2 (PFS2)

Definitions

PFS2: time from randomization (or start of initial therapy) to progression on the next line of therapy or death, whichever occurs first

captures both: duration of disease control on the initial (first-line) treatment (PFS1), AND duration of control on the subsequent therapy after progression

Time to progression (TTP) does not include deaths

Progression free survival (PFS) does include deaths; includes stable disease

Duration of response (DOR): only includes patients with an objective response to therapy

PFS Controversies

Used to be viewed as a good surrogate for OS; not always true now with multiple lines of therapy

Conversely, forcing wait for OS may delay approval

Possible biases:

Assessment of progression bias: due to potential treatment effects, true blinding may not be possible

Blinded Independent Central Review (BICR) of imaging can help overcome this bias

Assessment-time bias: the time point at which you discover a progression is when you will say progression occurs

Assessments in both SOC and experimental arms must be the same

Toxicities/Adverse Events

Standardly graded 1-5

Grade 1: mild; Grade 5: death

Grade 3+ considered “significant”

Treatments adjusted or discontinued at this level

Should compare AE rate of investigational drug to SOC therapy

Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) / Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

PROs are measured by PROMs - validated questionnaires

Help identify and characterize symptoms and toxicities, in addition to measurement of graded adverse events

Best practices

Be efficient and thoughtful about which PROMs you use - pts can experience respondent fatigue and clinical work flow can be burdened by over-collecting

Complement of PROMs should include a general QOL tool and a disease-specific PROM

General QOL PROMs

FACT-G (27 questions) and EORTC QLQ C30 (30 questions) best studied and most commonly used

Can add disease-specific scales - usually increases to ~60 questions

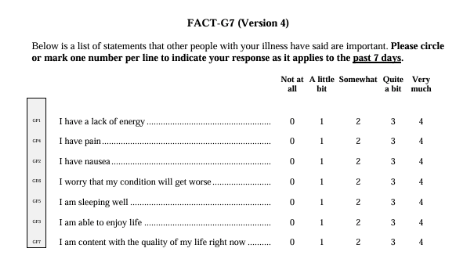

FACT-G7 (7 questions) over 3 domains - physical, emotional, functional well-being

Good for clinical use outside of trials

See Figure 1 for example

FACT-GP5: “I am bothered by the side effects of treatment”

SGO recommends the FACT-G7 + GP5 for use in routine clinical settings

Disease Sites

Ovarian Cancer PROMs

Disease-specific subscales from FACT or EORTC

NCCN/FACT Ovarian Symptom Index (NFOSI): 18-item measure

Uterine Cancer PROMs

FACT-G/FACT-EN (15 items)

EORTC-EN24 (24 items)

SGO states uterine disease is understudied in terms of PROs

Cervical Cancer PROMs

Heterogeneous group when comes to impact on QOL

Anxiety and sexual function concerns very relevant for this group even w/o disease recurrence

FACT and EORTC with cervical cancer add-ins

Vulvar/Vaginal Cancer

Stigma around these diseases so symptoms may not be spontaneously reported by patients

FACT-V (15-items) to add to general QOL PROM

EORTC is developing their scale

Additional Scales

Sexual Function

Up to 80% of female cancer pts report distressing sexual, vaginal, and/or menopausal concerns related to cancer and treatment; 90% say their oncologists don’t ask them about these things!

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) - 19 items

Modifiable for sexually diverse population and those who aren’t currently sexually active

PROMISE sexual function and satisfaction measures version 2.0 (PROMIS SexFS v2.0)

Appropriate for patients who are sexually active with or without a partner

EORTC - currently validating a 22 item QLQ-SHQ22

SGO recommended directly asking “would you like to discuss your sexual health?”

Biomarkers

Can be used as outcomes (biomarker change) or as inclusion/selection criteria for clinical trials

Predictive vs Prognostic Biomarkers

Prognostic: refers to the cancer outcome, independent of the therapy received

Predictive: whether the presence of a specific biomarkers impacts the chance of response to therapy

Quantitative Effect: both groups response to therapy but some get a better impact

Qualitative Effect: response vs no response

Proving biomarker is predictive can be challenging - need at least two comparison groups available, need to perform a statistical test for an interaction, and the test for interaction needs to be statistically significant

Clinical Trial Designs

Definitions

Integral biomarker: biomarker-defined criteria for enrollment into a trial

Integrated biomarker: used to test the hypothesis during the study, but isn’t a requirement for enrollment

Biomarker enrichment trials: only include patients with the biomarker expressed

Can reduce required sample size while maintaining power

Helpful if biomarker positivity prevalence is low

Randomized umbrella trials: target one disease of interest, with several different biomarkers being evaluated

Usually hierarchical/prioritized - one biomarker is the “prioritized” biomarker, and if a patient has that one, they’re triaged to that arm; if no, then check next biomarker

Example in endometrial cancer - RAINBO trial - for the different molecular subtypes of endometrial cancer

Basket trials: disease agnostic, test a specific targeted therapy on people w/ many types of tumors, as long as they have a specific biomarker

Example: DESTINY-PanTumor02

Clinical Trial Eligibility

Exists primarily to reduce the influence of confounding variables

Aims to identify the target population and make them similar at baseline

Aims to exclude people in whom toxicities are expected to outweigh benefits

Aims to follow regulatory guidelines regarding eligible populations

Aims to protect personal privacy

Aims to exclude patients who would not be able to comply with the planned intervention

Real-world Issues

Creating “ideal” populations can reduce the generalizability

Historically contributed to preferential enrollment of white patients from high SES who have less comorbidities or other reasons for exclusion

Comorbidity criteria

Tracking the relationship between accrual and comorbid conditions in clinical TRial enrollment (TRACE), Oluloro et al 2024

Aimed to characterize the comorbidity profile of patients with uterine cancer by race and compare w/ expected clinical trial enrollment patterns based on standard/historic Comorbidity Exclusion Criteria (CEC)

>284,000 patients included - 73% white, 14% black, 3% asisan

Odds of clinical trial exclusion based on comorbidities were 2x higher for black vs white patients w/ OR 2.09

Language

Often an exclusion criteria for enrollment

Even when not, still lower rates of enrollment for patients with limited English proficiency

Jorge et al. 2023

Enrollment rate 7.5% for English-speaking vs 2.2% for limited English proficiency

Best Practices for Discussing Clinical Trial Enrollment w/ Patients

Consider enrollments for all patients

Documented belief amongst medical providers that patients of color do not want to participate in research studies

Langfor et al. 2013 (Cancer)

No difference along racial or ethnic lines in clinical trial refusal rates or “no desire to participate in research” as a reason to refuse clinical trial

Common reasons pts decline enrollment

Discomfort w/ randomization and possibly receiving placebo

Fear of experimentation

Concerns about privacy

Time cost of the consent and monitoring process

Highlight values

Clinical benefit for them

Improving our knowledge of how to treat patients in the future

Increased knowledge about their own cancer/genetics

Core Principles

Trials should be offered to all eligible patients without preconceived assumptions about who might or might not be interested in participation

Clinicians should be forthcoming about both the limitations of their knowledge and the hopes informed by earlier phases of investigation

Transparency throughout the process is essential; while the ultimate outcomes of a trial cannot be predicted, patients should be provided with a clear framework of what to expect along the way

Figure 1.

FACT-G7 (7 questions) over 3 domains - physical, emotional, functional well-being; QOL survey

Reference List

1. Sisodia RC, Dewdney SB, Fader AN, et al. Patient reported outcomes measures in gynecologic oncology: A primer for clinical use, part I. Gynecol Oncol 2020;158(1):194–200; doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.696.

2. Sisodia RC, Dewdney SB, Fader AN, et al. Patient reported outcomes measures in gynecologic oncology: A primer for clinical use, Part II. Gynecol Oncol 2020;158(1):201–207; doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.03.022.

3. Anonymous. Vulva Cancer | EORTC – Quality of Life. n.d. Available from: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/qlq-vu34/ [Last accessed: 4/27/2025].

4. Anonymous. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) | NIH Common Fund. n.d. Available from: https://commonfund.nih.gov/patient-reported-outcomes-measurement-information-system-promis [Last accessed: 4/27/2025].

5. Ballman K V. Biomarker: Predictive or prognostic? Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015;33(33):3968–3971; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3651.

6. Oluloro A, Pike M, Moore A, et al. Tracking the relationship between accrual and comorbid conditions in clinical TRrial enrollment (TRACE). Gynecol Oncol 2024;190:S72; doi: 10.1016/J.YGYNO.2024.07.106.

7. Oluloro A, Temkin SM, Jackson J, et al. What’s in it for me?: A value assessment of gynecologic cancer clinical trials for Black women. Gynecol Oncol 2023;172:29–35; doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2023.03.002.

8. Jorge S, Masshoor S, Gray HJ, et al. Participation of Patients with Limited English Proficiency in Gynecologic Oncology Clinical Trials. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2023;21(1):27–32; doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.7068.

9. Montes de Oca MK, Howell EP, Spinosa D, et al. Diversity and transparency in gynecologic oncology clinical trials. Cancer Causes and Control 2023;34(2):133–140; doi: 10.1007/S10552-022-01646-Y/METRICS.

10. Langford AT, Resnicow K, Dimond EP, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical trial enrollment, refusal rates, ineligibility, and reasons for decline among patients at sites in the National Cancer Institute’s Community Cancer Centers Program. Cancer 2014;120(6):877–884; doi: 10.1002/cncr.28483.